By Dave Boulter

Executive Manager Pperations

Progression in gliding is rewarding – new qualifications, longer distances and new aircraft types are all part of the journey. However, accident and incident trends consistently show that risk increases when multiple new challenges are taken on at once or in quick succession.

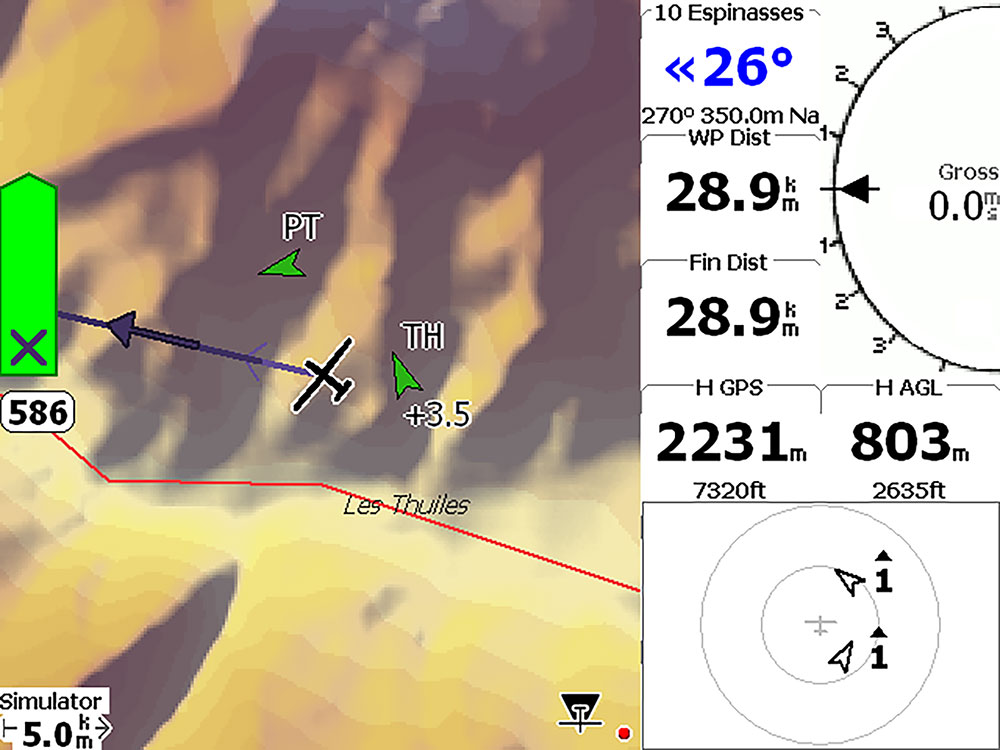

‘Pushing it’ rarely comes from poor intent. It more often arises from confidence growing faster than experience, combined with good conditions, peer pressure, time pressure or personal goals. Cross-country flying is a common pressure point. Extending distance, flying later into the day or pressing on in weakening conditions can quietly erode margins, particularly when fatigue sets in or landing options reduce.

Pacing Progress

Progression is most effective when it is paced. Club conversion steps exist to create space for learning, reflection and consolidation – not to be cleared as quickly as possible. Experience is built by flying in varied conditions, not by accumulating numbers.

Transitioning to different glider types demands adaptation in handling, energy management and systems awareness. Giving these transitions the time they deserve reduces workload, improves decision-making and supports long-term safe advancement.

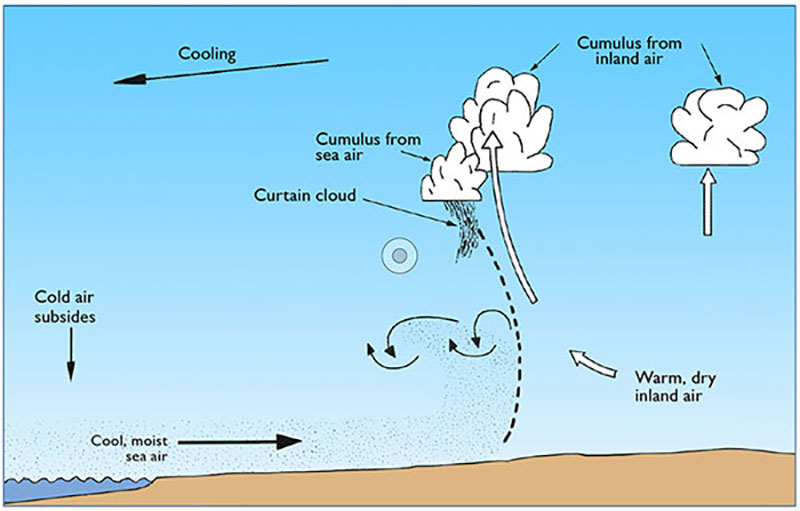

Strong days reward optimism. Marginal days punish it. Progressing rapidly through cross-country milestones without experiencing weaker conditions can leave pilots unprepared when lift, height and options are limited. Intensive flying periods, such as camps or strong soaring weeks, can compress experience. Pilots may achieve milestones quickly, but the real test comes when conditions are less forgiving. Without time to consolidate judgement across a range of days, the step from success to setback can be surprisingly small.

Marginal weather days demand conservative decision-making. Accident trends show that pilots often ‘push it’ on days that start well but deteriorate – pressing on rather than reassessing, diverting or stopping early.

When Slower Really is Faster

Fatigue and time pressure are underestimated risks. A lot of glider pilots take up flying later in life. With that comes a ‘time clock’ that is ticking. There are ‘bucket lists’. There is a sense of needing to achieve or have the chance to fly better performing aircraft before the clock stops. Unfortunately, fatigue can increase as we get older.

Instructors and coaches play a critical role. Well-intentioned encouragement can unintentionally become pressure if students feel the need to perform, progress quickly or meet perceived expectations. Good instruction balances challenge with consolidation. Allowing time to embed skills before adding new complexity builds safer, more resilient pilots.

A consistent message from accident reviews is that stacking transitions – new aircraft, new conditions, longer distances, unfamiliar terrain – significantly increases risk. GAus safety philosophy emphasises progressive learning, management of margins and conservative decision-making, particularly during periods of advancement or change.

A useful self-check for pilots and instructors alike is to ask:

“What is new today – and how many new things am I managing at once?”

Slowing progression is not a setback. Experience shows that slower is safer – and faster in the long run.

Getting the Paperwork Right

Paperwork isn’t the glamorous part of gliding. It doesn’t thermal, it doesn’t climb, and it never gets a mention in post-flying hangar review. Yet reviews repeatedly show that when paperwork slips, legal protections slip with it.

Let’s start with AEF flights. The AEF form must be completed before the flight, not afterwards and not “when we get time”. This is not optional. It is a regulatory, insurance, and duty-of-care requirement. If the form isn’t completed correctly, the flight should not proceed.

Tow pilots are no different. A valid flight crew licence, completion of the applicable syllabus, and formal approval by the EMO are required before towing operations commence. Until the paperwork is complete, the privileges are not valid.

Medical status is another recurring issue. All flight crew must have a current medical recorded in JustGo. If a pilot does not yet meet the requirements to be Pilot in Command, they may use a Not PIC medical, but they cannot fly solo until a valid medical is in place. No medical, no solo - simple.

Make sure that Maintenance Releases are filled out correctly. Check for any maintenance that must be completed on the glider before flight.

One common theme is documentation being uploaded incorrectly or not at all into JustGo. The instructions are clear, but they are often not read. It is lucky that reading instructions is not a test for pilots - but following instructions is still required.

None of this exists to create bureaucracy. These processes protect your friends and pilots, instructors, clubs and Gliding Australia itself. They ensure flights are legal, insured and defensible when things go wrong. They ensure your and your friends’ interests are met.

The message is straightforward: paperwork is part of safety. Getting it right enables flying. Getting it wrong stops it.

Take the time. Read the instructions. Upload the documents. Fly knowing everything is in order - in the air and on the ground.