Lessons in Managing Training

By Christopher Thorpe

Even the most experienced instructors can find themselves in situations where sound intentions collide with the unforgiving realities of aerodynamics and human performance. But just as important, inexperienced instructors – newly qualified, returning after time away or still building instructional judgement – can be even more vulnerable to the same traps. Gliding instruction is demanding work: it combines teaching, supervision, judgement and immediate aircraft management – often in the most time-critical phases of flight.

Instructors in their early instructional careers may still be developing the judgement that comes only from repeated exposure to varied students, changing conditions and time-critical decisions.

This is not a criticism. It is simply a reality of human learning: instructional judgement matures through experience, reflection and repetition – often gained across many seasons.

Australian gliding history includes fatal training accidents involving instructors of varying experience levels and very low-time students. Without dwelling on specific cases, the recurring patterns are highly relevant to every instructor and CFI. These events often begin with routine decisions made in routine conditions. The risk does not announce itself dramatically. It accumulates quietly – until the margin disappears.

This article is not about blame. It is about strengthening our collective safety practice by recognising common training traps that can affect any of us, and by reinforcing discipline in the phases of flight where there is no second chance.

Lesson 1: Timing the Transfer of Controls

One of the most important and least discussed instructional skills is knowing when not to hand control over.

Every student must ultimately fly each phase of flight. But not every moment is suitable for learning. A student may appear comfortable in smooth air at height, yet still lack the fine control, anticipation and speed awareness needed for high-consequence phases close to the ground.

A key principle

Learning opportunity must never outrank survival margin.

Competence vs exposure

A student can sound confident and look competent, particularly when the aircraft is stable and the workload is low. But competence is proven under workload, not in comfort.

Early-stage students are still developing:

- fine motor control (small inputs, not coarse corrections)

- relaxed grip and proportional response

- coordinated use of controls under pressure

- accurate speed perception without prompting

- calm scanning habits and task prioritisation

A small lapse – completely normal for a beginner – can become catastrophic at low altitude.

Experience cuts both ways

Highly experienced instructors sometimes take on extra workload because they can – monitoring, coaching, planning ahead and managing aircraft outcomes simultaneously. The danger is not competence. The danger is that the instructional task can expand to fill the available capacity until there is little margin left for surprise.

Less experienced instructors may face a different risk. They can be technically capable and diligent, yet still underestimate how quickly risk accelerates in the circuit, on tow, or in the flare. They may also be more likely to delay intervention while waiting to see whether a student will self-correct – particularly if they are trying hard to ‘give the student space’.

Neither pattern is a character flaw. They are common human tendencies. In both cases, the remedy is the same: disciplined training structure, clear gates for progression, and firm control of the aircraft whenever the safety margin is narrow.

The syllabus protects us

The GPC syllabus is deliberately staged to ensure that higher-risk flight segments occur only after students demonstrate repeatable basics.

Handing control to a student before they can reliably manage pitch, speed, coordination and workload does not accelerate training – it shifts risk into a zone where the instructor may not be able to rescue it.

Critical phases require instructor primacy

Some phases have very low tolerance for error, including:

- the initial seconds of a winch launch and the transition into the full climb

- top-of-launch and recovery after release (or any launch abnormality)

- early aerotow and positional deviations

- any unexpected event near the ground

- turn initiation at low level

- final approach and flare

- any flight below roughly 300–500ft AGL (context-dependent)

These phases are not the place for ‘letting them have a go’ unless the student has already demonstrated consistent control capability under supervision.

Confidence can be built at 2,000ft. Judgement errors at 50ft cannot be undone.

A simple test for hand-over safety. Before handing control over, ask:

If the student made a sudden incorrect input right now, could I reliably recover?”

“If the answer is “no” (or even “not sure”), then it is not yet time for the student to fly that segment.

Practical indicators that a student is ready include -

- they have recently flown the task successfully at altitude

- their control inputs are smooth and correctly scaled

-they maintain safe speed without continuous coaching

- they demonstrate a relaxed grip, not stiffness or tension

-they respond appropriately to surprise or workload changes. Recency matters. Repetition matters. Margin matters.

Communication prevents confusion

Control handover needs to be explicit and confirmed:

- “You have control.” (student responds “I have control.”)

- “I have control.” (student responds “You have control.”)

If I say “I have control”, you immediately release the controls and respond “You have control.”

I will respond “I have control”, to confirm the transfer is complete.

The most dangerous cockpit moment is one where both pilots think they are flying – or neither is.

No handover is complete until the receiving pilot confirms control and the other pilot confirms they are clear.

Lesson 2: Low Level Means No Second Chances

Gliders are remarkably forgiving when we have altitude and time. They are brutally unforgiving when we don’t.

At height, we have -

- time to recognise errors

- space to correct attitude and energy state

- a recovery window if the aircraft departs the ideal path. Near the ground, those options disappear.

In soaring we trade altitude for time. At low level, you have neither.

The height–time equation

A glider on a winch launch, on aerotow at a few hundred feet, or on short final, is in a compressed world where:

- airspeed decays quickly if mishandled

- control inputs have immediate consequences

- bank angle reduces stall margin dramatically

-the instructor’s intervention may come too late – even when correct. This is not about skill or diligence. It is about physics outrunning humans.

Distraction and overload close to the ground

Some of the most dangerous instructional situations are not caused by poor technique but by a sudden, unexpected distraction at low altitude, just as workload is peaking.

A minor abnormality can instantly become a major threat if it occurs at the wrong time. Attention is pulled away, priorities blur and the instructor becomes overloaded – especially if they are still gaining confidence in real-world instructional flying.

This is precisely the environment where startle effect and task fixation can override training. People do not rise to the occasion – they often fall back to whatever response comes first under pressure. In the wrong moment, even a well-trained instructor can forget his or her training, not because they don’t know it, but because human performance temporarily collapses under overload.

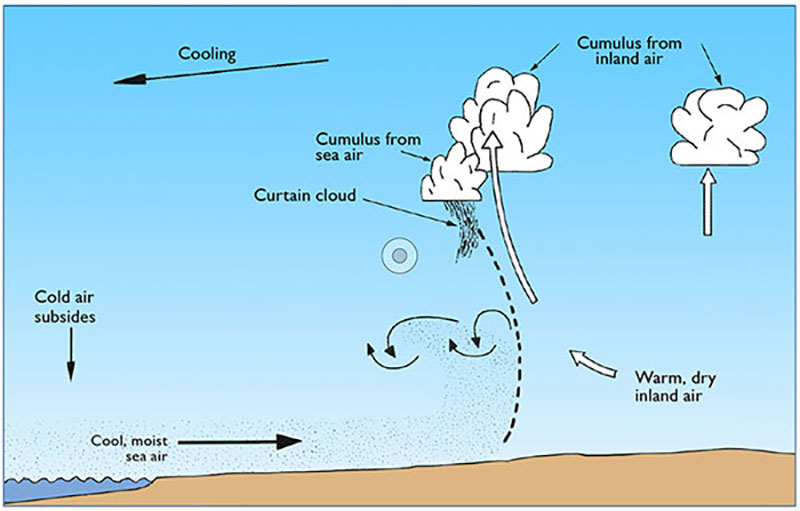

Why ‘straight ahead’ is drilled

The gliding community has long emphasised straight-ahead landings after low rope breaks and stable wings-level approaches. These are not conservative habits – they are survival strategies.

When altitude is limited

- turning costs energy

- correcting costs time

- recovery requires height

At low level the only reliable currency is speed plus stability.

The low-level turnback trap

One of the most consistent fatal traps in low-level emergencies is the attempted turnback.

It usually starts with a real problem – something unexpected that demands attention – followed by a rushed decision to save the situation with a manoeuvre that requires height, speed and mental bandwidth.

But at low altitude, a turnback

attempt often produces

- increased bank angle and reduced stall margin

- loss of airspeed control while attention is divided

- delayed recognition of the developing stall

- insufficient height to recover

Instructors should treat the turnback impulse as a known human trap, an understandable decision made under pressure, but frequently unrecoverable when started too low.

The correct response must be not just known, but automatic: Fly the aircraft. Keep it safe. Commit to a survivable landing path.

Lesson 3 - Instructor Defensive Posture

In a glider, the instructor has fewer escape tools than in powered training. There is no go-around. There is no throttle to buy time. At low level, the instructor’s primary safety tool is immediate and decisive control of the aircraft.

Defensive posture is not mistrust. It is professionalism.

‘Ready’ must be physical, not theoretical

Defensive posture means

- hands positioned to take full control instantly

- feet ready for immediate rudder authority

- a scan that prioritises attitude, speed and trajectory

- a mental state primed for intervention

At low altitude, ‘I’ll fix it if needed’ is not a plan unless you are already positioned to act.

Shared control at low level is high risk

Shared control – student flying pitch while the instructor manages airbrake – can be useful training at height, where there is time to fix problems. But near the ground One phase. One pilot. One purpose.

If the student is not yet reliably holding speed and attitude, the instructor should fly the approach and flare until that skill is stable and repeatable.

When in doubt, fly it out

Hope is not a safety tool.

A disciplined instructor does not wait and see if a student will correct a developing low-level risk. If there is doubt about speed, attitude, bank or alignment: Take control early

Taking control early

- prevents negative training

- maintains the safety envelope

- models professionalism

- protects confidence in the learning environment

For instructors early in their careers, this point deserves emphasis. Decisive intervention is not ‘overreacting’. If anything, instructors tend to regret intervening too late far more often than intervening early.

Lesson 4 Human Factors and Training Judgement

Instruction is a human factors task as much as it is a flying task. Students bring motivation and enthusiasm, but they also bring predictable beginner vulnerabilities:

- tense grip and coarse inputs

- fixation and tunnel focus

-startle response and delayed processing

- task saturation and freeze behaviour These are normal and expected in early training.

Instructors, regardless of experience, are still human too. They manage:

- aircraft control

- student supervision and interpretation

-circuit management and lookout

- constant anticipation of errors

All of these items must be handled while operating without power reserves, and often in time-critical phases. Low altitude exposes every human limitation at once.

Judgement is the instructor’s core skill

Instructors make constant micro-decisions

- Is the student relaxed or tight?

- Are they ahead of the glider or chasing it?

- Is this exercise consolidating success or inviting surprise?

- Is this the right moment to hand over – or the right moment to pause? Good judgement often looks like restraint:

- repeat consolidation rather than ‘progress’

- end the flight on success rather than ‘just one more try’

- delay low-level practice until skills are proven at height

For newer instructors, this restraint can feel uncomfortable. There is often a quiet internal pressure to demonstrate competence, to progress the student, to keep the flight moving and to get it done.

But training safety is not achieved by pushing the envelope. It is achieved by expanding it only when the student is ready.

A culture that supports instructors

A mature training culture is one that supports instructors as well as students. That support includes:

- mentoring for newly qualified instructors

- shared briefings on local hazards and what catches people out

- encouragement to debrief honestly, without embarrassment

- clear standards from CFIs about handover height and intervention expectations

- consistent messaging that safety comes before progression

New instructors do not become good by being left alone. They become good by being supported.

The Takeaway

Fatal training accidents are rarely caused by negligence. More often, they reflect an accumulation of small, understandable decisions where the margin quietly disappears – particularly when close to the ground.

Gliding instruction is an act of stewardship. We pass on not only technique but also habits and discipline that shape how pilots fly for decades.

The most valuable lessons we teach are not manoeuvres. They are:

- patience and timing

- early recognition and early correction

- energy and margin protection

- calm control under workload

- respect for low-level reality

Good instruction is not measured by how quickly a student is pushed forward, but by how safely and confidently they progress.

We honour those lost by absorbing these lessons – and strengthening our standards – one flight, one student and one disciplined decision at a time.

INSTRUCTOR TAKE-HOME CHECKLIST

5 RULES

1) Training Risk: Low Level, High Workload, No Second Chances

Protect the margin - don’t hand over control unless you have enough height, time and recovery space.

2) Low level = instructor primacy

Below an agreed height: you fly unless competence is proven and repeatable.

3) Surprise = Aviate, Commit, Land

If something unexpected happens: fly the aircraft first, choose the safest option early, and

land ahead if low.

4) Turnback is a known trap

Treat the low-level turnback impulse as hazardous – avoid unless clearly safe and trained.

5) Intervene early, not late

If doubt exists about speed, attitude or trajectory: TAKE CONTROL and stabilise.

About the Author

Christopher Thorpe is the former Executive Manager Operations for Gliding Australia and has extensive experience in aviation safety, training and gliding operations management.

This article is provided as an educational resource for the gliding community.